Meet The Colourist

Special Interview with Ben Gervais

Technical Supervisor, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk

Programming, broadcast engineering, and camera assisting, first in my native Canada, now in Hollywood. I’ve worked in post for a while. When digital cameras came along, I started helping DoPs with workflows. Whenever someone wants to push new technology into a movie, like 3D or some sort of special effects, I try to help.

I’ve worked on a broad range of projects, but often I’m on cutting edge features, like Hugo or Pacific Rim. And most recently I’ve spent two years working with Ang Lee on Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk.

I was originally supposed to work on Life of Pi, but Hugo ran over schedule. When Ang got the go-ahead from Sony for Billy Lynn he said he wanted to shoot high framerate 3D. He had some ideas and the studio had some technical people, but he wanted a second opinion from someone who was thinking primarily about the movie and the overall end-to-end workflow, not just post. I was referred to his producer by a producer I had worked with: we met and just kind of hit it off.

The first was the schedule. We only had a 49-day shooting schedule, and we had to fit a war in there. Not to mention a football game and its halftime show. It really became about finding, at every stage of the project, how we could make things quicker – on set, in dailies, and in editorial – and more tightly integrated, along with post, so we’d fix any possible issues wherever it was most efficient to do it.

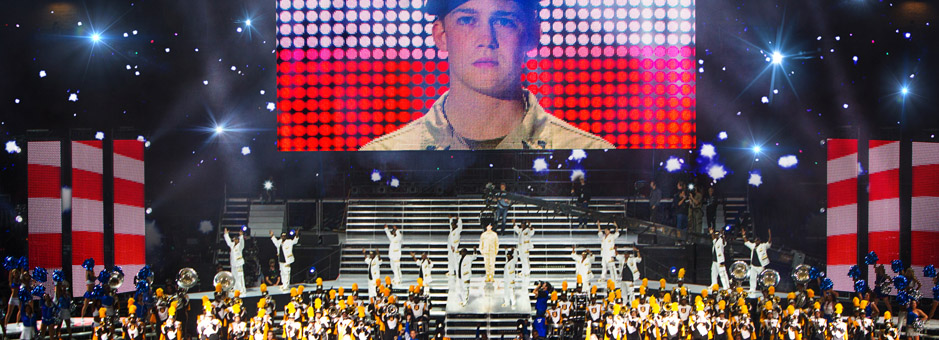

The big talking point around Billy Lynn is the technical format.

Working with the studio, we decided to shoot at 120 because that would give us the flexibility to create the multiple formats that would be shown in theatres. Then we can generate 60 because it’s exactly half the frame rate, and we can generate 24 because it’s a fifth.

We just thought it was a good source format, but Ang likes to push boundaries and he wondered what watching the film in 120 would look like. No one had ever seen it before. With the help of Christie Mirage digital projectors, and media servers from 7thSense Design, we tried it – and it blew our minds. When the lights came up after we saw it the first time, we were all just sitting there stunned. We knew we had to show this to audiences, because it’s remarkably different to what people are used to seeing.

The first thing was figuring out how to conform a movie combining 120 frames-per-second with 3D in HDR, which basically meant how to handle an incredible amount of data. On a typical shooting day we would capture an average of seven and a half terabytes, so we needed to have a workflow to copy that off the cards, back it up, calculate a checksum, copy LTOs and create dailies. And that pipeline had to be failsafe, so that we didn’t get swamped if something broke. Nathan Shields, a documentary editor who worked as a 3D lab technician on this project, helped me a lot prepping and testing all this, as did the rest of the lab team - Derek Schweickart, Michael Buck and Daniel George.

We finally put together our own system, three parallel pipelines, each using various bits of proven software. And we found we were able to turn around a full day’s worth of dailies in 12 to 18 hours. We didn’t think we would get it all done that quickly, but we put a lot of thought into it and made it work.

Why was the very high frame rate so important to Ang Lee? How did it affect the look?

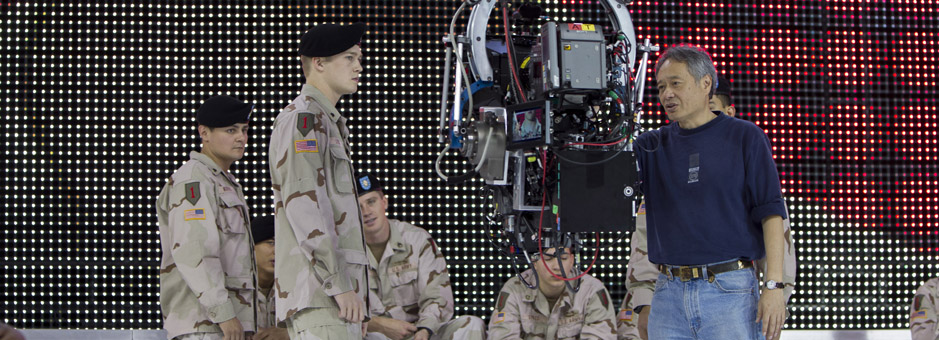

Ang wanted a very realistic, natural look. The high frame rate means you see much more than you would normally see in a movie. He wanted to immerse people in Billy’s experience.

Ang and John Toll went for a flatter, more natural look as the light didn’t have to be so contrasted or dramatic. And we didn’t really use make-up on the actors – the only actor who has a lot of make-up is the cheerleader, and that’s because she would have a lot of make-up in real life.

Most directors who shoot war scenes use slow motion, but because the format is so sharp, Ang decided to just let the camera sit and the action play out in front of it. So realism was the guide for the look. What does the heat of Iraq feel like, when it is so damn hot that the light is oppressive? That is something most people never get to feel.

Who else was involved into the film?

Tim Squyres, long-time editing partner of Ang Lee, who is technologically very savvy. Tim likes working in 3D: he claims to have only seen Life of Pi in 2D twice in his life. It means he is keeping an eye on the stereo and the convergence all the way through the editorial process. Editing the world’s first 120fps 3D movie was another opportunity for him to push his technical creativity.

For Billy Lynn, we created our own DI lab, which was a first. Many talents joined us, like the guys I mentioned earlier: Nathan Shields, Michael Buck and Daniel George were all 3D lab technicians for the prep and dailies, while Eyal Dimant worked with us in post too. Demetri Portelli was our stereographer, and he concentrated mostly on the on-set workflow and then in post he supervised the 3D. Derek Schweickart, who I had worked with on Resident Evil and Hugo, joined us as well as our DI Conform Supervisor. VFX artists were ‘in house’ too, using NUKE and rendering shots straight onto the Baselight system.

Adam Inglis was the main colourist, but because he was busy, we ended up having him for only four weeks. Now on a normal movie that would be all you would need for DI, but we ended up needing much more. So Adam set the looks for the full 120fps 4K 3D version. Inglis’s colleague Marcy Robinson carried out the final grade, and Doug Delaney handled additional grading for the Dolby Vision HDR versions.

How did you choose to work with FilmLight?

Ang was insistent that we do the DI, especially the main version, in 4K 120 stereo and so at that point, I looked at every vendor to see who could provide a system that plays back real-time 120 frame 4K stereo. FilmLight were really the only people who stepped up to the plate.

We used three Baselight systems during production, mostly just to playback dailies, and the premier Baselight X for DI.

Once we actually got the Baselight X in, we discovered that the system could handle a lot of what we needed to do in conform too, which really saved us in a lot of ways. For example, frame blending, which we had to deal with a lot because we were experimenting with having different frame rates in the same scene. We were using an external software package to do that but it also needed 50 frame handles. So how do we take a completely conformed movie and expand every shot with 50 handles? It just so happens that Baselight's Timeline Sort tool has that ability.

Baselight X can play back both eyes at 4K 120fps and at the same time allow creative multi-layer grading plus 3D geometry correction. By providing the very high frame rates for real-time uncompressed playback as well as interactive grading, Baselight X provided a pretty smooth creative and immersive experience.

I think what I like most is the flexibility of the tools in Baselight. You can trick them: trick is maybe the wrong word, but it is extremely flexible. Whatever the problem we ran into, we would say ‘there must be a tool on Baselight that lets us do this’ and usually after a little bit of searching – this is a very complicated tool as well as powerful – we would find that thing, whatever it was.

A good example came from our in-house VFX artists rendering into the Baselight directly. We would get through a lot of versions very quickly: as soon as they would version up we would have it. I wrote a lot of custom code to track versions, EDLs and more. I thought it was going to be really tricky to keep track. Then I thought, what if we put a Baselight wildcard in an EDL?

I was pretty sure it was going to break it, but we did a test and it worked. It would match all the versions of that VFX shot, and it would ask us which one we wanted to use. Things like this make for really handy time-saving. They simplify and speed up what you are trying to do.

We used the Baselight for a lot of viewing, too, because we had pretty much instantaneous feedback, which made DI on the 120-frame version possible.

Add to this flexibility the recognition that Baselight stereo tools are solid and let us do pretty much everything that we wanted to do, and of course as a colour tool it is one of the best. So all around Baselight checked every box for us.

I’m interested in FilmLight’s BLG concept moving forward, too; maybe see how 3D features will integrate more next. A cloud platform to store information and keep all the different BLG versions synchronised would be neat too.

How would you summarise your experience on this project?

The word that comes to my mind is ‘complexity’; I think just for cinema delivery we have something like 12 or 16 versions of the movie and then in terms of the actual amount of data we were capturing, that was obviously challenging. I think we have about 160 terabytes sitting on the Baselight X, with visual effects, camera negative, and so on.

Working with Ang Lee is amazing. He really responds to an image, he just looks at the faces on the screen and says this one feels more comfortable or less comfortable, more intimate or less intimate. He's also a very visually adept director, very sensitive almost to the point where he would surpass some colourists. There were some days where he would come into the dailies studio and ask what I’d done and all I’d done was re-calibrate the projector. He's a treat to work with because of that, because he’s so sensitive to what he sees.

I’m just finishing up the deliverables on Billy Lynn. Then Ang’s next movie, I think.

Join In

If you want to participate in our MTC programme, we'd love to hear from you. Contact:

Alexa Maza

e: [email protected]

“When the lights came up after we saw it the first time, we were all just sitting there stunned. We knew we had to show this to audiences, because it’s remarkably different to what people are used to seeing.”

Details

Colourist: Ben Gervais

Role: Technical Supervisor

w: Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk