Peter Postma, Managing Director Americas, FilmLight

VFX and editing have been possible in the cloud for a while, but colour correction presents some unique challenges.

At a Showcase Theatre session at IBC2022, Katrina King, Content Production Media & Entertainment, AWS, said: “Ingesting assets to the cloud without the ability to finish is essentially a bridge to nowhere.”

We at FilmLight are delighted to have had the opportunity to work with AWS on cracking some of these challenges and we look forward to presenting more on this topic at NAB 2023.

Find out more about where we’ll be at NAB 2023 »

What is colour correction?

Colour correction is the final creative step of the film making process. It’s the last chance to make any tweaks or adjustments to the image before it’s finalised and sent for distribution in all its various forms. In essence, it’s the last chance for the cinematographer, producer and director to have their final input in what the image is going to look like.

It’s called colour correction because the primary task is adjusting the colour, tone and texture of an image. It’s completed in real-time, so a colourist is usually receiving fast feedback on what they’re doing.

It’s likely, too, that trailers and release dates are already being marketed and that there is a set date for distribution that needs to be hit. This means there is usually not a lot of time to complete the finishing touches and the colourist will need to be interactive and work quickly.

Sometimes the changes are quite small and centre around the correction of things that happened on set. This could be, for example, fixing a scene that was supposed to take place over just a few minutes, but in reality was shot over the course of several of days. The requirement here would be to make the images consistent and cohesive, like it all happened at once. Or, perhaps, the colourist is making more dramatic color changes to really affect the emotion of the piece and enhance the story telling of the images.

However, colour correction is often referred to as digital intermediate (DI), colour mastering or picture finishing, stemming from the fact that it’s often not just colour changes being made, but light VFX work, too – like smoothing out wrinkles on people’s faces, sky replacements, removing a boom from a shot or similar adjustments that can now take place in a grading suite.

Our colour corrector at FilmLight is called Baselight. This is where the colourist will bring all their high-resolution final footage to put those final touches in at the highest possible quality, before it goes out for distribution. To help with speed, the colourist might also be working with one of our control panels, such as the Blackboard 2, which gives them all the functions of the Baselight software at the push of a button.

Why colour in the cloud?

Traditionally colour correction is completed on premises with hardware onsite. So why would we want to move it into the cloud?

The first reason is flexibility. The impact of COVID-19 has changed the work dynamic for production facilities and increased the need for remote working solutions. Operating in the cloud allows a colourist to work remotely so they do not always need to be in the post facility. They may choose to be there for much of the grade, but it’s common in post-production for a colourist to be waiting for the last few VFX shots or a title to drop in before they can make the finishing touches. Having the option to operate in the cloud means they do not need to sit around the facility while they wait for what they need and allows them to make the final edits remotely if required.

The second reason is scalability. The cloud allows post houses to quickly deploy additional instances and hardware resources – allowing a post house to grow when they have more work coming in and shrink when demand drops. It also lets them scale their hardware to the job. For example, if they are doing a regular HD finishing of a commercial that’s SDR, they don’t need hardware that’s as powerful as if they’re delivering a 4k feature film.

It’s unlikely, though, that they’ll want to do most of their post-production the traditional way and then just move into the cloud for colour correction. However, when all other parts of the workflow are in the cloud it doesn’t make sense to upload and download assets to grade locally – it would make more sense to leave everything in the cloud.

A traditional colour session

A typical colour session today takes place in a dedicated grading suite – a room that’s purpose built for colour correction. It will have a carefully calibrated monitor or projector and a colourist working at a control panel, often with the director, producer or DoP next to them so they’re all looking at the same image as they work through the adjustments.

Traditionally it’s done with dedicated hardware on-site as it’s the fastest most robust way to do it. This is particularly true for high-end productions when the team might be working with 8K source material and finishing in either 4 or 8k.

To colour correct at such high resolutions, the colourist requires fast image processing. This is why our local hardware system has multiple GPUs in it so that it’s able to process multiple frames at a time and is able to play back at a speed of typically 4k 24fps or higher.

The other reason it’s good to have local hardware is that it provides very low latency. When a colourist is adjusting the control on a knob, they need to see the image changing right away. If there is any kind of lag, where the colourist stops turning and the image keeps adapting, it will slow down their creative process. This low latency requirement was one of the key challenges when working on the colour in the cloud ‘project’.

The final thing the colourist needs is a proper viewing environment, with a monitor that is properly calibrated so that they can trust what they’re seeing matches the reference standard. And they will need an uncompromised signal to the monitor. This does not necessarily mean it must be uncompressed, but the compression should not compromise the colourist’s judgement of the image, as part of their role is to complete a quality check.

If the colourist spots any problems with the image they will need to identify where it’s coming from. For example, artifacts could be inherited from the source footage, which they may need to go back and fix, or consider using a different take. It might be that the grade has brought something out, particularly when working with VFX if the grade that the colourist applied has started to pull apart the composite and show the edges of the seams. Or, it could be something to do with how they’re monitoring the images. So, if they’re monitoring a compressed output and seeing artefacts, this could interrupt and slow them down as they won’t be sure if the artefacts are in the source material or in how they’re viewing it.

HEVC streaming

We have a tool built into Baselight called Client View, which uses H.265 or HEVC streaming, to allow the client to remotely view the image. So, when a DoP or a director for instance is not able to be in the room with the colourist, they can have an iPad pro or a calibrated SDI monitor where they can see the image streaming from the Baselight. And we include a thumbnail overview for them, for metadata, so they can make real-time notes for the colourist, flag shots and scroll through the timeline while the colourist is working. HEVC compression works very well for this because it doesn’t require a lot of bandwidth to achieve a good image. It’s not completely uncompromised and there will still be some compressions artefacts, but it provides a very high-quality image that the DoP or director can make judgement on and provide commentary regarding the direction they want to take their piece.

One of the ways that HEVC is able to achieve these high data rates is by using interframe compression. This means it’s looking at multiple frames and checking where pixels don’t change that much from frame-to-frame, or checking key object movements and copying pixels as opposed to sending them every time. This means it’s very efficient for compressing a video stream, but it does introduce latency as you have to wait for multiple frames to be rendered before you can look at the motion across those frames and send them along.

This works well for a client session where the colourist may make a change and say to the DoP or director, “how does that look?”, as in the second that it takes the colourist to ask the question, the DoP or director already have the updated image. This second or two of latency is OK for working with the client, but when the colourist is adjusting the controls they need to be fully interactive – a second or two of latency is going to slow down the creative process.

The other problem with HEVC is that most of the available hardware and software for dealing with it, particularly the chips built into the in-video GPUs, do not support 12-bit, which is a requirement for HDR.

Other edge artefacts will also be visible in HEVC compression. You can adjust the data rate of HEVC to try to avoid these, but if you want a really uncompromised image which the colourist can depend on, it’s better to have a compression algorithm that minimises these as much as possible.

A big part of colour correction is also on the texture of the image. It’s not just about the tonality and the colour, it’s looking at things like how sharp are the eyes; what does the grain look like in the image; how smooth is the skin; how are the lights and the halation in the image; or, are we trying to mimic film or be sharp like digital. And the subtlety of these things are one of the first things to go with these compression algorithms, so it’s important to protect for this as well.

JPEG-XS

This is why we’re using JPEG-XS codec for image reference streaming in our implementation with Amazon. It’s high bit-depth, allowing 10- and 12-bit compression; it’s low latency and doesn’t even require a full frame to be rendered in order to start compression, keeping any lag or latency to a minimum. It’s also visually lossless at good compression ratios, producing 4:1, 5:1, 6:1 compression and still achieving that uncompromised image with no artefacts.

There is also support for mathematically lossless so if you do have the bandwidth you can go to a completely lossless option in the future.

AWS/FilmLight finishing in the cloud

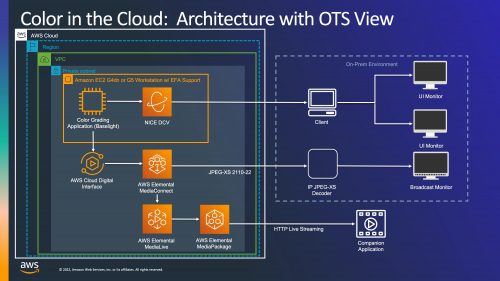

To meet the many requirements of being able to colour correct in the cloud, AWS has repurposed its Cloud Digital Interface (CDI), originally built for broadcast, to transport video in the AWS cloud. To get from cloud to on-prem it uses AWS Elemental MediaConnect which supports JPEG XS over ST2110-22, partnering with Riedel and Evertz on the decoders.

“We have achieved the ‘over the shoulder feel’ for uncompromised live reference-grade monitoring,” said King. “We now want to see this workflow used for compositing, master QC and any workflow that can benefit from cloud-based reference monitoring.”

We at FilmLight have been testing this solution with AWS over the past few months, with several studio partners to develop the technology further.

NAB

FilmLight’s Peter Postma, colourist Lou Levinson, and Marlon Campos from AWS will explore this topic further at NAB 2023, in a SMPTE Floor Session titled “Remote Collaborations – Colour Grading in the Cloud”. It will take place on Sunday 16 April at 1pm in the West Hall (#W3421). For more info on this session, visit NAB.

Baselight is also part of a colour in the cloud workflow demo on the AWS stand at NAB (W1701).